Alexander Hamilton, Founding Statistician

Regular theatergoers have heard the actor portraying Aaron Burr ask: How did Alexander Hamilton,

“dropped in the middle of a forgotten

spot in the Caribbean by Providence impoverished in squalor

grow up to be a hero and a scholar?”

Hamilton: An American Musical traces Hamilton’s life from an orphan in the West Indies to George Washington’s aide-de-camp, co-author of the Federalist Papers, first Secretary of the Treasury, and finally, duel casualty. For some reason, however, the musical never mentions Hamilton’s key role as one of the founders of official statistics in the United States. Hamilton was one of the first persons — possibly the first — to submit statistics calculated from administrative data to Congress.

Paying the Bills of the Revolutionary War

In 1789, the newly independent United States badly needed revenue. Debts incurred during the American Revolutionary War amounted to more than $75 million dollars, and the American government had already defaulted on loan installments due to France in 1787.*

It’s not surprising, then, that the second Act of the first U.S. Congress, from July 4, 1789, involved a method for collecting revenue.** There was reluctance to levy domestic taxes in a country that had just fought a long war on the principle of “no taxation without representation” and the Act proposed collecting duties on imported goods. It stated: “Whereas it is necessary for the support of government, for the discharge of the debts of the United States, and the encouragement and protection of manufactures, that duties be laid on goods, wares and merchandises imported” and proceeded to specify duties of ten cents to be collected per bushel of malt, fifty cents per pair of boots, ten cents per pound of snuff — and so on, for about 80 categories of merchandise from tea to buttons to pickled fish.

That Act, however, did not say who should collect the duties. On July 31, 1789, the Congress clarified that it was the duty of the customs collector “to receive all reports, manifests and documents made or exhibited to him by the master or commander of any ship or vessel”; moreover, the customs collector was to “make due entry and record in books to be kept for that purpose, all such manifests and the packages, marks and numbers contained therein” (U.S. Congress, 1845, p. 38, emphasis mine). Collectors were to “keep fair and true accounts of all their transactions” and “once in every three months, or oftener if they shall be required, transmit their accounts for settlement” to the appropriate department.

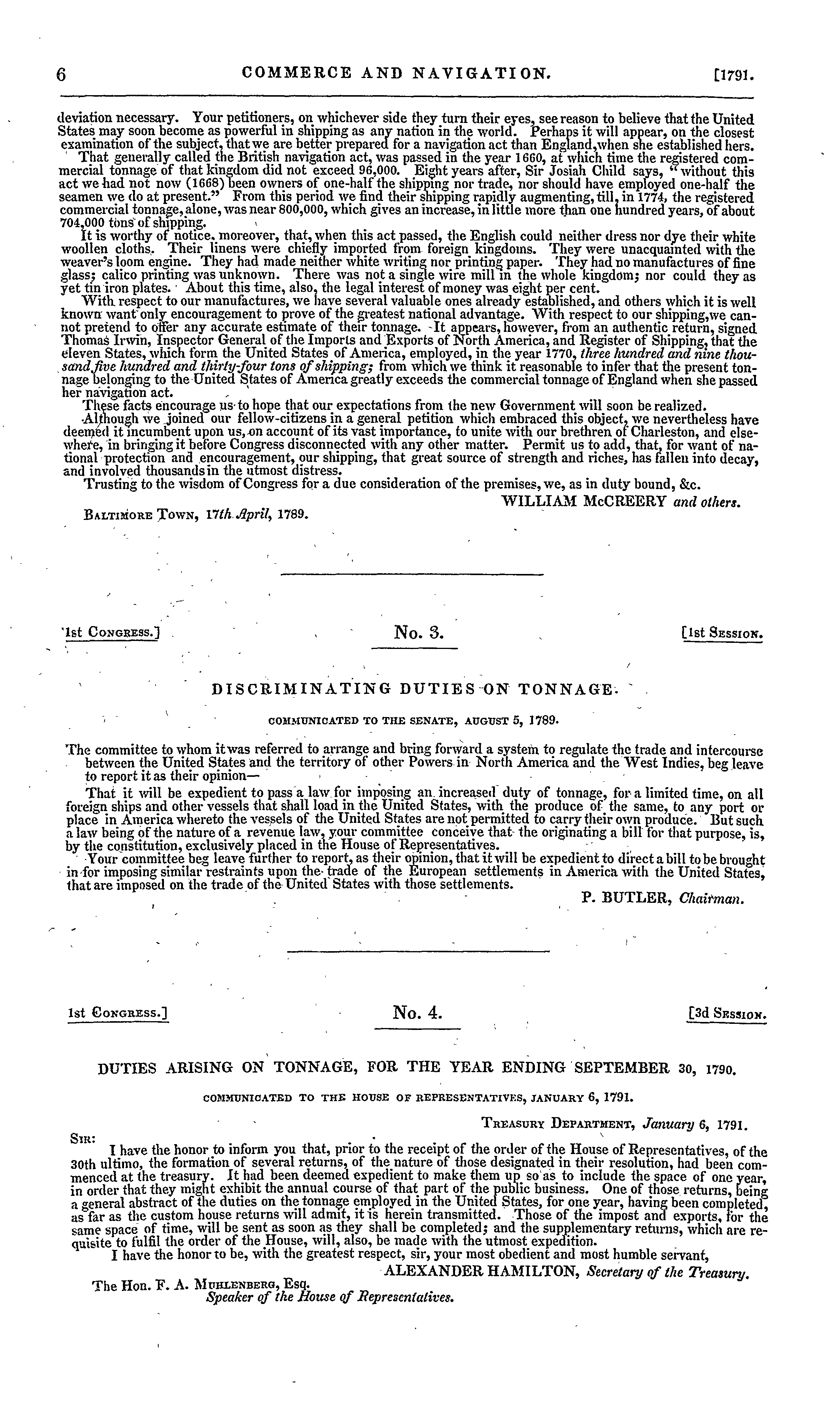

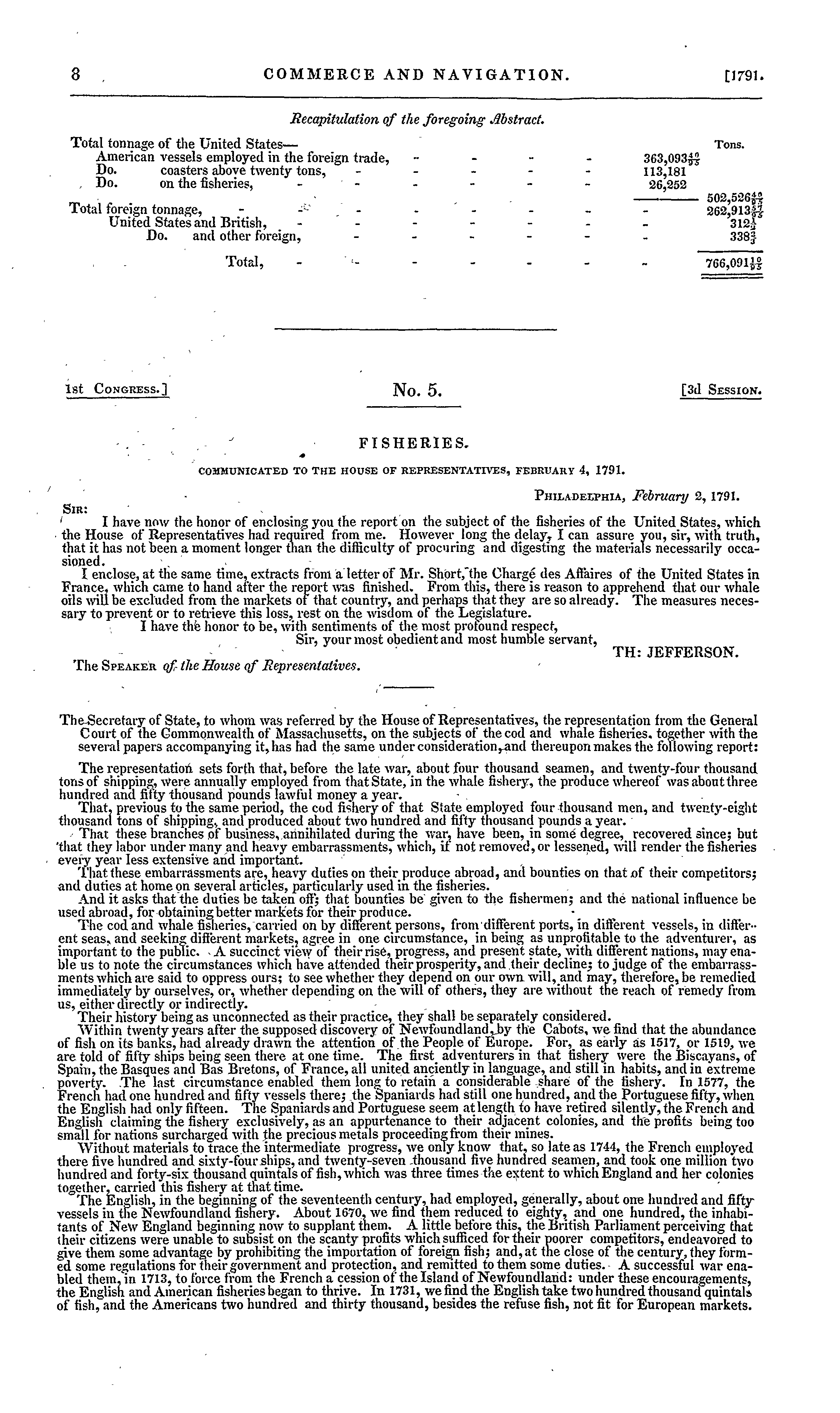

This is the first data collection mandated by Congress, and it established a series of statistics about foreign commerce that continues to this day. Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton submitted the first report to Congress on January 6, 1791: “a general abstract of duties arising on the tonnage of vessels entered into the United States, from the 1st of October, 1789, to the 30th of September, 1790” (Hamilton, 1791).

Hamilton’s Report

Hamilton (1791) tallied the tonnage and duties received in each of the 13 states, and categorized those amounts by the nationality of the vessel carrying the goods (see Figure 1). Hamilton’s footnotes on page 7 highlighted one of the challenges he encountered when preparing his statistical summary — three of the states had missing data. Rhode Island and North Carolina began submitting returns midway into the year, and the last-quarter report from Charleston, South Carolina had not yet been received even though more than three months had elapsed since the end of the quarter.

Figure 1. Hamilton’s 1791 report on duties received. Source: Hamilton (1791).

The problem of missing data persisted in Hamilton’s subsequent reports on foreign trade (and continue to be a problem for administrative data collections). For example, his February 15, 1791 report on “Exports for the year ended September 30, 1790” noted “a deficiency of many of the returns for the last quarter of the year 1790, which confines the abstract to the 30th of September last.”

Legacy

Many people date the U.S. federal statistical system to the first decennial census in 1790, but one can argue that it actually started with Hamilton’s submission. Data collection for the first census began in 1790, but the enumeration took more than 18 months to complete. Preliminary results were transmitted to Congress in October 1791 and partial results were published in 1793 (Anderson, 2015). Hamilton’s report in January 1791 preceded the census statistics by nine months.

Moreover, the first census was riddled with errors and both George Washington and Thomas Jefferson were highly skeptical of the results. Hamilton paid careful attention to the quality of the data, and clearly knew that his statistics were only as good as the data that fed them. He included caveats about the limitations of the statistics he produced, noting in the February 15, 1791 report that his statistics were “abstracted from customs house returns” — he did not say that these were the true values of the exports.

Cummings (1918) traced the explosion of statistics calculated from administrative data that followed Hamilton’s initial reports. Today, government agencies are looking for new ways to take advantage of currently existing data to produce useful statistics, continuing a tradition that Hamilton established more than 230 years ago (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2023).

Hamilton’s statistical contributions were not limited to reports from the Treasury Department. He and James Madison argued the necessity of a decennial census in the Federalist Papers. Essay 36 proposed using a census of population to apportion taxes among the states and essay 54 discussed using the census to apportion delegates in the House of Representatives to the states.*** Hamilton also devised a method for performing the apportionment that was used between 1850 and 1900.

Francis Amasa Walker, welcoming members of the International Statistical Institute to Chicago in 1893, commented that "a strong passion for statistics" developed early in the United States and listed Hamilton as one of the early statistical pioneers.**** "Statesmen and publicists, like Alexander Hamilton, … not only founded their theories of economics and taxation inductively, by the use of the best statistical data available, but exerted their powers to extend the field of exact knowledge and became working statisticians, so far as their imperfect training and the inadequate agencies at their command would allow" (Walker, 1894, p. xxxvii).

Perhaps a new song is needed: How a man with Hamilton’s characteristics became a founding father of American statistics.

Copyright (c) 2023 Sharon L. Lohr

Footnotes and References

*Calculating the equivalent value of the loans in today’s dollars is challenging, since 1913 is the first year for which Consumer Price Index data are available. The CPI measures price levels that consumers pay for a “market basket” of goods and consequently provides a measure of changes in prices (inflation) over time (Nagaraja, 2020, outlines the history of the CPI and explains how it is measured). Historians and economists have estimated CPI-equivalents for earlier years; the inflation calculator at https://www.in2013dollars.com/ estimates that $75 million in 1790 equates to about $2.5 billion in 2023 dollars. Daggett (2010) estimated that the total cost of the war had been $101 million in the dollars of the time (about $3.4 billion in 2023 dollars).

**The first Act of the first Congress involved the time and manner of administering the oath of office to members of the House of Representatives. This act specified that the oath of office would be administered by the Speaker of the House to other members — and set the precedent that other members could not be sworn in until a Speaker was elected, as occurred in January 2023.

***The 85 essays in The Federalist were written between 1787 and 1788 by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay and published anonymously under the pen name “Publius.” Hamilton and Madison later prepared lists claiming authorship of specific essays in The Federalist. Hamilton’s list, which became public shortly after his death in 1804, claimed more than 60 of the essays, including essay 36. Madison’s list, published after his term has president, he had prepared became public, claimed to have written more than 60 of the essays. The problem in ascribing authorship was that 12 of the essays (numbers 49-58 and 62-63) were on both lists — these became known as the “disputed” essays.

Statisticians Frederick Mosteller and David Wallace (1963) applied Bayesian discriminant analysis to study authorship of the disputed papers, using counts of common words as the variables for discrimination. For example, in works with known authorship, Madison used the word “by” about twice as much as Hamilton. Mosteller and Wallace concluded, on the basis of the word frequencies, that Madison wrote all 12 of the disputed essays. Note, though, that the Library of Congress lists “Alexander Hamilton or James Madison” as the author of The Federalist number 54 and it is possible (even likely) that Hamilton provided ideas or collaborated on essay 54.

****Francis Amasa Walker was one of the preeminent American statisticians of the 19th century. He superintended the 1870 and 1880 decennial censuses, was one of the founding members of the International Statistical Institute, and served as president of the American Statistical Association from 1883 until his death in 1897.

Anderson, M. (2015). The American Census: A Social History, 2nd ed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Chernow, R. (2004). Alexander Hamilton. New York: Penguin.

Cummings, J. (1918). Statistical work of the federal government in the United States. In Koren, J. (Ed.), The History of Statistics. New York: Burt Franklin, pp. 573-689.

Daggett, S. (2010). Costs of Major U.S. Wars. Congressional Research Service Report 7-5700. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

Hamilton, A. (1791). Report on duties arising on tonnage, for the year ending September 30, 1790. In American State Papers: Commerce and Navigation, Volume VII (pp. 6-8). Washington, DC: Gales and Seaton. The collection is available online through the Library of Congress at https://memory.loc.gov/ammem/amlaw/lwsplink.html.

Lohr, S. (2022). Sampling: Design and Analysis, 3rd edition. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. Page 118 discusses Hamilton’s method for apportioning the House of Representatives.

Mosteller, F. and Wallace, D. L. (1963). Inference in an authorship problem: A comparative study of discrimination methods applied to the authorship of the disputed Federalist Papers. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 58(302), 275-309.

Nagaraja, C.H. (2020). Measuring Society. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2023). Toward a 21st Century National Data Infrastructure: Enhancing Survey Programs by Using Multiple Data Sources. Washington DC: The National Academies Press.

U.S. Congress (1845). Public Statutes at Large of the United States of America from the Organization of Government in 1789, to March 3, 1845. Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown.

Walker, F.A. (1895). Discours du général Francis A. Walker, président-adjoint de l’Institut international de statistique. Bulletin de l’Institut International de Statistique, 8, xxxvi-xxxix.